Cognitive semiotics addresses a fundamental question: How can we come to know the world through signs and languages? This question lies at the heart of several debates in semiotics, philosophy, and cognitive science, especially those concerning subjectivity, representation, belief, perception, imagination, social cognition, mind, and language.

The term “cognitive” is not intended to contrast with emotion or passion. On the contrary, forms such as fear, emotion, and feeling are all considered cognitive. They contribute to our ability to know the world, echoing a Peircean view that resists any strict opposition between intellect and affect.

Umberto Eco once remarked: “The theme I have addressed in an almost obsessive way, throughout all my work, is that of how we come to know the world”. His exploration of fictional worlds—where truth must be uncovered, constructed, or grasped through blurred contours—reflects a consistent effort to understand how signs function as tools of knowledge. “My work in semiotics,” he noted, “concerns the problem of how our signs give account of that which is or construct that which is not”.

In line with this view, Claudio Paolucci argues that cognitive semiotics is not a specialized branch of semiotics but its very vocation. “The object of cognitive semiotics,” he writes, “is the way in which semiotic systems represent the background of our perception of the world and define the conditions under which cognition and knowledge are possible.” This approach sees signs, texts, and languages not as secondary expressions of thought, but as the very forms that make thought and knowledge possible.

This conception goes beyond traditional distinctions between signifier and referent. When Saussure, Hjelmslev, and Greimas argued that meaning does not reside in the extralinguistic world, they were pointing to the role of language as a cognitive framework: a system that organizes perception and extends our capacity for knowledge.

Peirce expressed a similar view when he claimed: “It is far more true that the thoughts of a living writer are in any printed copy of his book than that they are in his brain” (CP 7.365). This formulation anticipated contemporary theories of extended cognition, where thought is distributed across media, signs, and artifacts. To study texts, signs, and languages is therefore to study cognition itself.

Cognitive semiotics examines how signifying processes support both understanding and action. It proposes that meaning is not a passive reflection of the world, but an active process of sense-making. Texts and languages do not express pre-existing thoughts: they constitute the very form of thought. They serve as cognitive scaffolding, enabling perception and knowledge to emerge.

This theoretical stance engages directly with current debates in the cognitive sciences. Many of today’s researchers, often unknowingly, confront semiotic questions—whether in the analysis of perception, emotion, or narrative—without necessarily framing them as such. For cognitive semiotics to play a meaningful role in this context, it must articulate a strong theoretical position, one capable of informing both semioticians and cognitive scientists seeking reliable insight into meaning and cognition.

Cognitive semiotics aligns with several traditions of thought. It integrates Radical Enactivism, Pragmatism, and Material Engagement Theory. It reframes the classical philosophical issue of subjectivity through the concept of impersonal enunciation. It introduces the notion of a semiotic mind, grounded in Peirce’s theories and characterized by habits, beliefs, and representational practices. It also investigates social cognition, highlighting how narrative structures help interpret others’ actions and account for phenomena such as autism spectrum disorders.

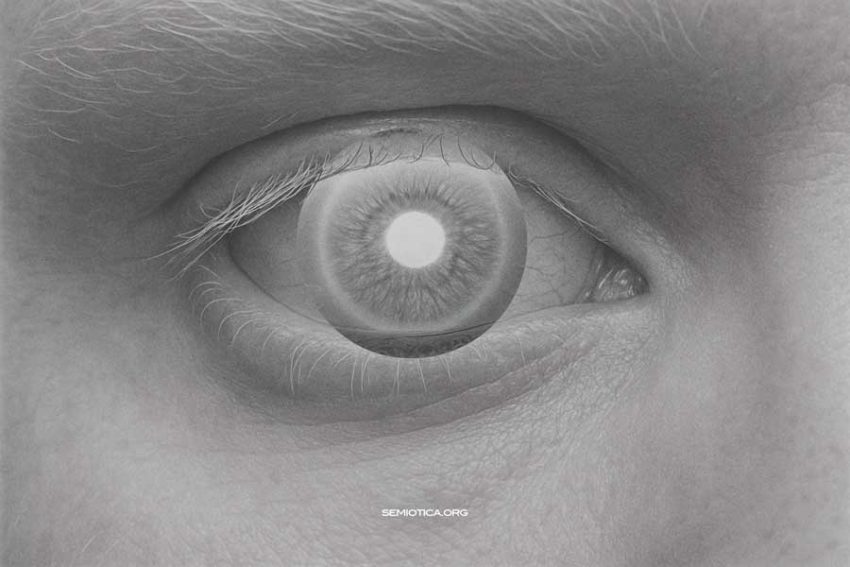

Perception is approached not as a passive intake of sensory data, but as controlled hallucination or controlled figuration. Theories such as predictive processing and Goethean models of vision are reinterpreted through the lens of semiotics, with special emphasis on the role of imagination.

Ultimately, cognition is seen as:

- An enactive process of interaction with the environment;

- A form of action mediated by meaning and interpretive habit;

- A dynamic structured by semiotic systems, which condition how reality is apprehended and constructed.

Through this framework, cognitive semiotics reveals itself as both a theory of knowledge and a philosophy of sense-making, rooted in the very structures that allow us to inhabit and interpret the world.

Reference: Claudio Paolucci, Cognitive Semiotics: Integrating Signs, Minds, Meaning and Cognition, Preface, 2024.